This article first appeared in The Early 202 newsletter. Not a subscriber? Sign up here.

Last year was the least productive year in Congress in at least 50 years.

This year is on track to be worse.

It’s an election year, which often makes Congress skittish about doing things, like passing bills. And Republican implosions this past week don’t bode well for the rest of the year and are leaving many members angry and frustrated.

With Trump almost certainly at the top of the ticket, Republicans are following his cues.

An inexperienced and overwhelmed House speaker, Mike Johnson (R-La.), is facing constant rebellion from the right flank of his party, which is threatening to remove him from his job. Plus, Republicans are growing anxious that they will lose the House, in large part because they have nothing to show for their majority.

Johnson had a particularly bad night:

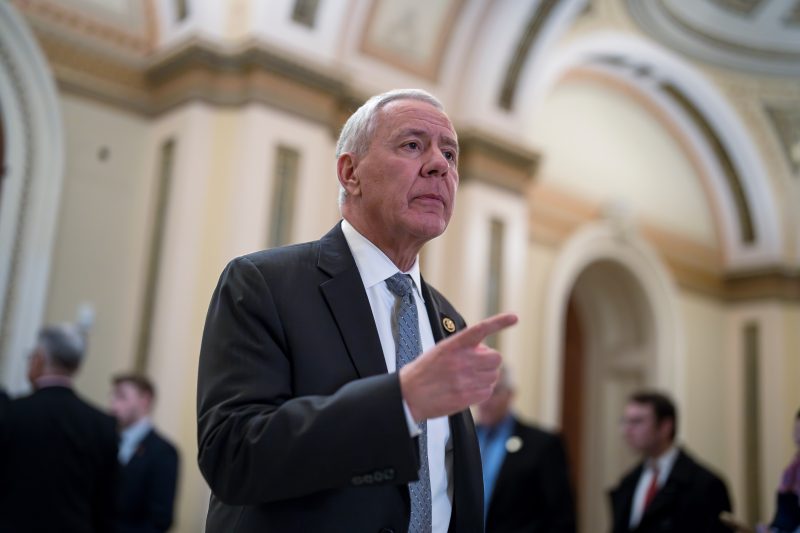

Republicans failed to impeach Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas after three Republicans — Reps. Ken Buck (Colo.), Tom McClintock (Calif.) and Mike Gallagher (Wis.) — voted against it. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) had originally pushed impeaching Mayorkas as a ploy to appease the Republican base.

Johnson failed in his effort to get the House to pass $17.6 billion for Israel and to replenish U.S. weapons systems without aid for Ukraine. It was an attempt to pressure the Senate, but far right lawmakers rejected that plan because it’s not paid for and Democrats saw the move as political opportunism.

But that’s not all.

Congress is five months into the current fiscal year and has been unable to fund the government for more than a few weeks or months at a time. The next funding deadline is March 1. There is no clear plan on how to fund the government after that. Between now and then, the Senate will leave town for two weeks and the House will be in session for just eight days.

“I just think that everyone is using logic from previous congresses and previous experiences, and thinking, ‘Well if we do this, that will happen.’ And I just don’t think in the 118th Congress you can try to figure out what the other side is going to do,” Rep. Jared Moskowitz (D-Fla.) told our colleague Abby Hauslohner. He added that the only things this Congress is known for are “removing a speaker and expelling a member.”

Last year, Congress passed just 29 bills that were signed into law. Many of them were minor. It also raised the debt limit and extended government funding multiple times. As for the House, it censured Reps. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) and Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.). It also expelled Rep. George Santos (R-N.Y.).

The House did achieve a recent success, passing a bill to restore some of the Trump tax cuts and expand the child tax credit and a low-income housing tax credit. But that package is being slow-walked in the Senate and its eventual passage is uncertain.

There has also been little legislating in the Senate. The days are mostly filled with votes on nominations.

But the latest iteration of Congress’s deep dysfunction has been on display with the immediate collapse of a bipartisan border security deal. It took four months to come up with a plan — a nearly impossible feat — and less than 48 hours to shelve it.

Republicans had originally demanded changes to border policy. Democrats said they entertained the demands. The result was $20 billion for the border and the most stringent border security policy changes in decades.

But Republicans walked away. Just three Republicans publicly backed it: the lead negotiator, Sen. James Lankford (Okla.); the appropriator who co-wrote the funding portion, Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine); and McConnell.

Because of that, military aid for Ukraine and Israel is in question.

A furious Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) had this to say:

“These people made very explicit demands and then abandoned what they said are their core values because their leader Trump told them what to do. That is nuclear grade incompetence and legislative malpractice,” Schatz said. “It will be hard to rebuild trust.”

Even some Senate Republicans acknowledge the challenging times and are frustrated with the dynamics of their party, the slim majorities and the election year politics.

“There’s a lot of dysfunction,” Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.) said. “We haven’t done much.”

Sen. Todd Young (R-Ind.) called the last four months “instructive.”

“We don’t have an obligation to attempt the impossible,” Young told reporters. “And it appears that some things that my colleagues on a bipartisan basis were working on are now impossible.”

Congressional Republicans are becoming less able to govern, as their members increasingly represent the far right. The most conservative members of Congress have a skinny legislative track record.

According to an analysis by the Center for Effective Lawmaking of the last 50 years of legislating, “conservative Republicans in both chambers are notably less effective than their moderate Republican counterparts in advancing their bills, even when Republicans are in the majority party,” write the authors of the report, Patrick W. Buhr and Alan E. Wiseman of Vanderbilt University and Craig Volden of the University of Virginia.

The analysis doesn’t include the current Congress, where the most conservative Republicans have been unsuccessful in passing legislation but successful in blocking it.

As our colleague Paul Kane recently wrote, Johnson has had to use a tactic to bypass an ongoing blockade from the right “that regularly tries to sabotage the normal flow of legislation if it’s deemed insufficiently pure for conservatives.”

It’s called suspending the rules, and it requires two-thirds support to pass legislation. Johnson has used it half a dozen times in his short tenure on major bills.

“That two-thirds requirement effectively means Johnson and Republicans give away their negotiating leverage because Democrats know that their votes are decisive in the very narrowly divided House,” Paul writes.

Johnson used the tactic last night to try to fund Israel. It failed.

“This is what happens when you try to govern based on suspension,” Rep. Bob Good (R-Va.), the chairman of the House Freedom Caucus, which opposed passing Israel aid without corresponding spending cuts. “This was a terrible mistake.” (In Johnson’s defense, he only used suspension because Good and other Republicans refused to vote for it.)